Rosalia Namsai Engchuan: Building Other Grounds

Artist, anthropologist, and curator Rosalia Namsai Engchuan discusses her personal artistic journey exploring mixed heritage, crypto-colonialism, and healing practices, as well as her work with Bangkok Kunsthalle's Futures Observatory program.

Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Q: Hi Rosalia, thank you for your time. You have a very multifaceted profile: anthropologist, artist, curator at the Bangkok Kunsthalle and more recently part of the team of the St. Moritz Art Film Festival and now TONO in Mexico. While these aspects of your practice are more or less interconnected, I would like to start with your work as an artist.

There are several recurring elements in your work, including colonialism, the role of women, and epistemicide. However, what seems to tie these themes together is a more intimate inquiry stemming from your mixed German and Thai heritage. It is a personal journey that began in Germany at Berlin's "Thai Park" with Complicated Happiness, and continued with Elusive Homes and Energy Bodies in Thailand. If this perspective makes sense, where do you feel you are currently situated within this personal and artistic research?

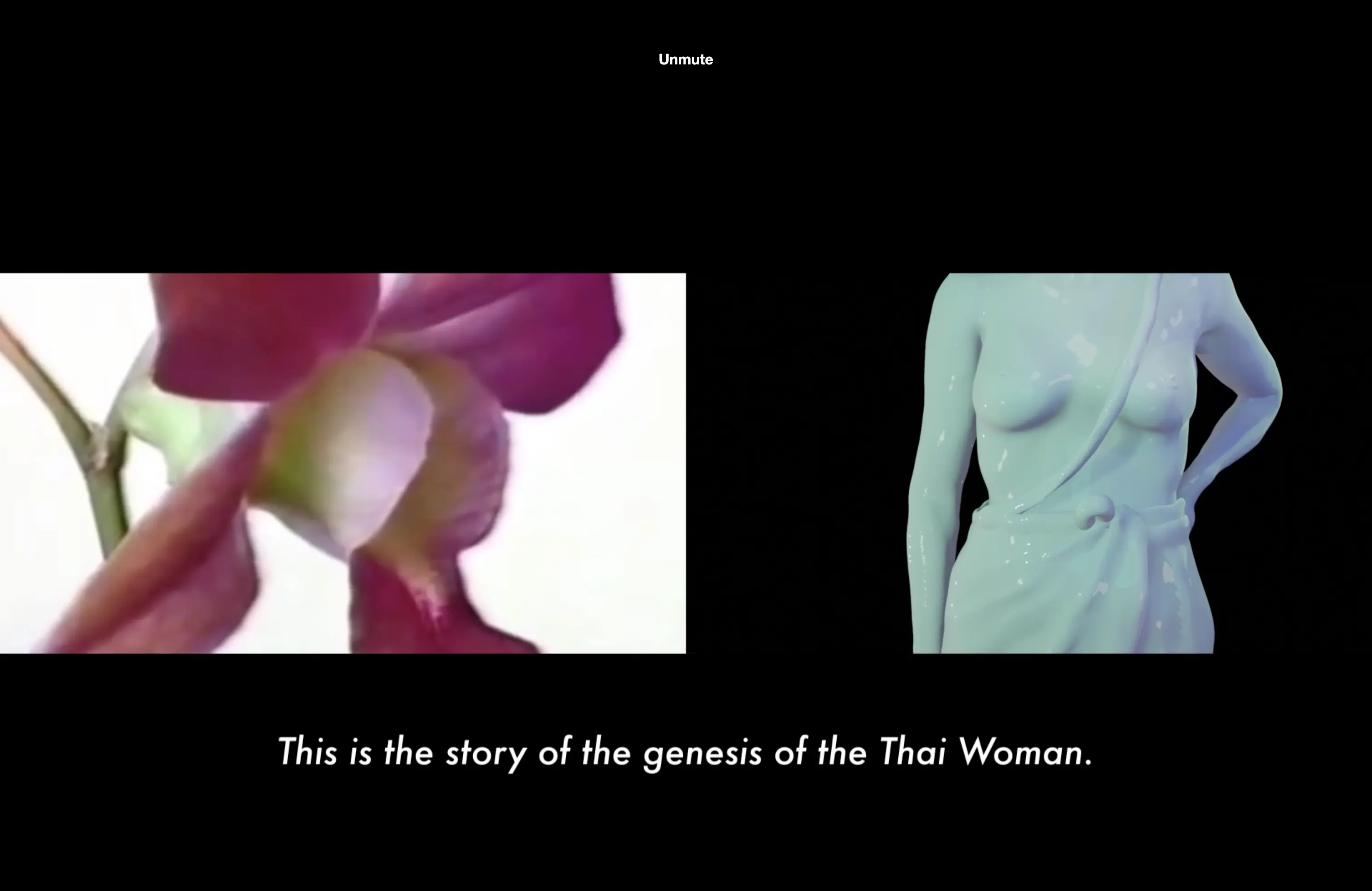

Thank you for seeing the personal thread. It's absolutely there. Art for me was about creating spaces where I could externalize what I didn't want to carry any longer. My first work came from a place of anger. In On Thai Women, which engaged Jean Baudrillard's writing on Thai people (in awful stereotypes). I took a very confrontational approach. I was responding to an image that had shaped how I was seen and, in some ways, how I had learned to see myself.

The project around Berlin's Thai Park marked a shift. I moved from reacting personally to listening more closely to how stereotypes were structuring other people's lives: their work, their relationships, their sense of self. With Elusive Homes, the lens turned both more intimate and more historical. The film weaves together my father's migration journey to Germany, plantation workers from Myanmar in Thailand's Deep South who build small spirit altars, a termite shrine, and Thai women who enter monastic life in Berlin and become caretakers of the most beautiful flower gardens and a colony of bird-houses turned spirit shrines. What holds all of that together in a very intuitive way for me is the idea of home and what that might mean. It's a very personal film, but it's also about broader conditions of displacement, belief, and belonging.

Complicated Happiness. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Complicated Happiness. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Complicated Happiness. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Energy Bodies was a turning point. I made it when I was already living in Thailand, and I began to feel that simply opposing stereotypes wasn't enough. I became more interested in what existed before: the cosmologies, healing practices, and relational ways of being that had been there long before these reductive images took hold. That led me into conversations with Thai healers and into researching the arrival of modern medicine in Siam. Instead of only critiquing the stereotype, I started looking for what I think of as its antidote. And that's where the figure of the midwife/shaman became central.

My conversations with Tarini Graham, a traditional midwife, became the basis for holding the world between, an installation and critical archive shown at Ghost 2568 curated by Amal Khalaf, and it continues in my writing, including my essay for CONG. It marks the beginning of a longer journey for me. I'm less interested now in working only against dominant narratives and more interested in expanding the frame of the archive, of knowledge, of what we even consider reality. As long as we stay in a reactive position, we're still orbiting the same center. I'm trying to build other grounds from where to do things. Over the years, I've gathered a massive archive. Not just from institutions, which are often problematic, but from conversations, rituals, observations, and lived experiences. Where I am now is holding space for these materials and practitioners to speak to each other and to resonate with other contexts, especially across the Global South.

Energy Bodies. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Energy Bodies. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Q: One of the recurring themes in your work, spanning both your art and essays such as You Only Think I Love You Long Time, is how the relationship with the West has imposed societal shifts through what you describe, citing Michael Herzfeld, as a form of "crypto-colonialism." This includes changes in beauty standards, gender differentiation, and the depiction of women as submissive figures, but also extends to childbirth rituality and the capitalist commodification of healing practices. Today, Thailand is experiencing a moment of particular popularity internationally, not only due to tourism but also regarding its representation in the mass media. Do you believe this has an impact on the local art scene? Is there a risk of a loss of identity in the exercise of finding a balance between the local and the global?

Thailand is having its White Lotus moment. This is not simply a shift in image but a shift in fantasy. The figure of the submissive Thai woman is fading from mainstream circulation (because honestly it got boring), replaced by another projection: Thailand as a site of luxury healing, spirituality, and lush landscapes. On the surface, this might appear like progress or a return to tradition. But it remains a fantasy economy, for those who can afford it.

The country is now staged less as a body to be consumed and more as a landscape to be inhabited. In many ways, this moment of hyper-visibility can be understood as a new phase of Herzfeld's crypto-colonialism: a subtle alignment with external expectations, gazes, markets, and desires. The underlying structure persists as Thailand merely functions as a backdrop for the emotional and spiritual dramas of others.

Obviously a profound denial underlies this image. The problems we are facing in terms of environmental degradation, labor precarity, and social inequality rarely enter the frame but they are here and they won't go anywhere. The question is not only about representation but about the economic and ecological systems these representations help to sustain. I guess what I am saying is that Thailand does not need more global attention, but perhaps its own little wellness journey inwards, like listening to its people, its histories, and the lands that sustain us.

Energy Bodies. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

So I am not concerned about a loss of local identity. The idea of a pure, bounded identity is a colonial fantasy. Thailand was cosmopolitan and in exchange with other places, people and ideas since forever. Just look at traditional Thai medicines and how it was shaped through exchanges with Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, Khmer traditions and many others. What I am very concerned about is the dominance (both materially but also in terms of imagination) of a deeply limited and extractive model of life: never separable from capitalism, patriarchy, and racial hierarchies. This logic really took over the world and it did not simply "modernize" Thailand; it reorganized social life, landscapes, and cultural production around what can be made profitable, legible, and exportable.

The risk is not that artists lose their identity—identity is always multiple and formed in relation (thinking here with Glissant)—but that artistic practice is pulled toward marketable aesthetic surfaces with no stakes and no soul and detached from everything that sustains it.

So much is happening in Thailand right now and so many new initiatives are forming so the local art scene is very much still up for grabs and always in the making and I have hope and am actually quite excited.

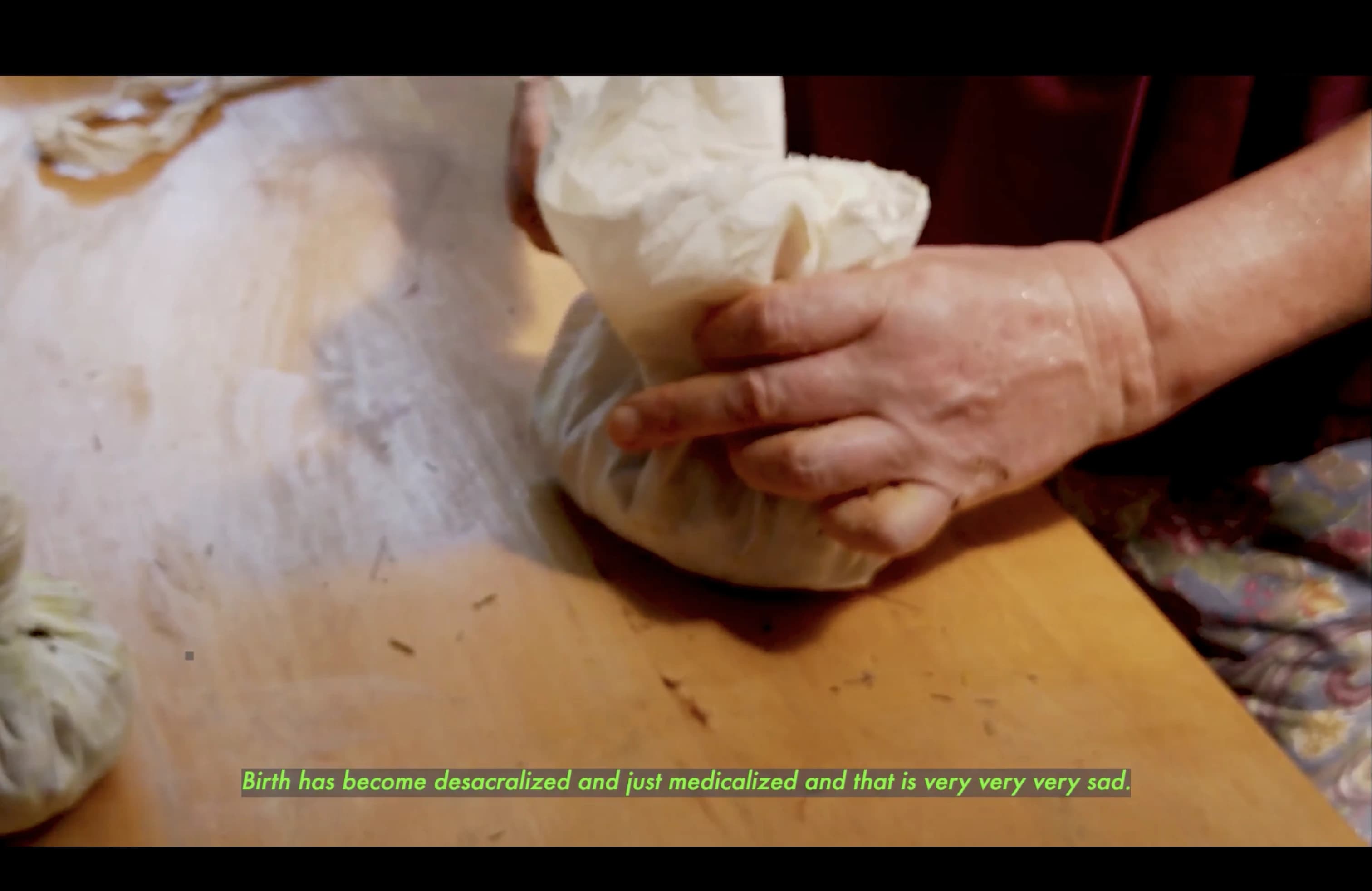

Elusive Homes. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Q: Continuing on the topic of the relationship with the West, childbirth and its practices play a major role in your work Elusive Homes. One of the aspects you focus on is how childbirth in the West, while offering women the safety of modern medical science, seems to have lost not only traditional rituals but also its connection to the community. I find this particularly relevant in an era where those speaking most about children and birth rates are primarily men (such as Elon Musk, who has made the depopulation of the West one of his propaganda battles). They discuss it either in merely numerical terms (viewing children as future consumers and funders of the current generation's pensions) or, in the worst case, through a conflictual relationship with an "otherness" that must be stopped, such as immigrants. How do you perceive this subject these days and within your current context, being a mother yourself?

Becoming a mother has been the best thing ever. My daughter is my greatest teacher. It has radicalized me, because these things I have been writing about are no longer abstract! I quite literally carry my heart outside my body now. Interdependency is no longer just a philosophical idea; it's an embodied reality. So in the most beautiful way she made me a deeper version of myself, like more myself.

Birth is not a statistical event, it is a process and the beginning of a cycle. In many traditions, birth is not just medical but relational and cosmological. A newborn is introduced through the steam of the plants to the sensory language of the land. Embodied and molecular environmental consciousness that was weaved into birth rituals (not only in Thailand). That kind of beginning shapes how a person understands themselves in relation to others and to the environment. While modern medicine has undoubtedly saved lives, it has also displaced many of the communal, spiritual and ritual dimensions of care that are not only different births but a different consciousness for world-making.

In that sense, I sometimes think the most direct form of future-building I can engage in right now is simply how I raise my child and try not to shape her into an obedient participant in extractive systems, but into someone who understands interdependence. Today entire industries have formed around replacing very basic forms of care and communal knowledge with purchasable solutions: specialized beds, baby monitors, formula and extremely costly expert advice on everything relating to the basic question of how to care for your child. Choosing more relational forms of care can suddenly appear radical.

That, to me, revealed how deeply care itself has been reorganized under capitalist logics and why reclaiming it feels so urgent. Care is political. And this is not only a question for mothers, but for all of us. The world needs a mother. And when I say this I don't mean a person or a gendered role, but a way of loving and taking responsibility that is unconditional.

Elusive Homes. Credits: Rosalia Namsai Engchuan

Q: With the Bangkok Kunsthalle, you started working on the Futures Observatory program about a year ago, also inviting entities outside the Kunsthalle to become part of it. Could you tell us what it focuses on and how it is progressing?

The work with the Kunsthalle is, in a sense, an extension of your artistic research, or perhaps a fusion of your artistic and academic sides. How do you see these two different facets of your work in the future? Is there a direction you feel more oriented towards?

I am answering both of these together:)

The work I do at Bangkok Kunsthalle and through Futures Observatory is really another articulation of the same questions that run through my artistic research, just in a more collective and space-holding form. Through my role at the Kunsthalle I feel particularly fortunate to be able to invite more people directly into those conversations.

Futures Observatory began from a simple but urgent shift in perspective: what happens if we think about the future not from a Euro-American framework of progress, crisis, or technological acceleration, but from a Southeast Asian situatedness? The project asks how we might relate to the future differently? Not through prediction or fear-based control but through offerings.

Bangkok Kunsthalle. Photo: Andrea Rossetti

In practical terms, this takes the form of gatherings that bring artists, healers, researchers, and local communities into shared processes. Moving image plays a central role here, because cinema allows us to sit together in time and to rehearse different ways of sensing and being. For example, in Paradiso with Oat Montien, we focused on queer Southeast Asian artists, their grief, and their dreams. We also hosted a collective hypnosis session led by artist and hypnotherapist Julia E. Dyck together with her partner, sound artist Liew Niyomkarn, where participants were invited to meet their future selves. Moments like this bring many strands of my work and passions together. Situated within an art space they are oriented toward the collective rather than the individual. These are, in a way, experiments in de-commodifying wellness, asking what happens when such practices become shared tools for being together in an unwell world. Upcoming programs, like an astrology-focused event with Parinda Mai and the Braty collective, continue this exploration.

This is also where the artistic and academic sides of my work meet most clearly. The research into healing practices, cosmologies, and relational knowledge systems informs the conceptual frameworks, while the events themselves are the social spaces where these ideas are rehearsed and embodied. Rather than moving toward either a purely academic or purely artistic direction, I feel more oriented toward building and holding spaces where different forms of knowledge can coexist.